By John Danner, Faculty Partner

Every organization strives to create meaningful value from the resources it has available while it trying to prepare for an uncertain future. In large organisations, that becomes a very complex matter, with competing and conflicting performance measures, terminologies, and even cultures.

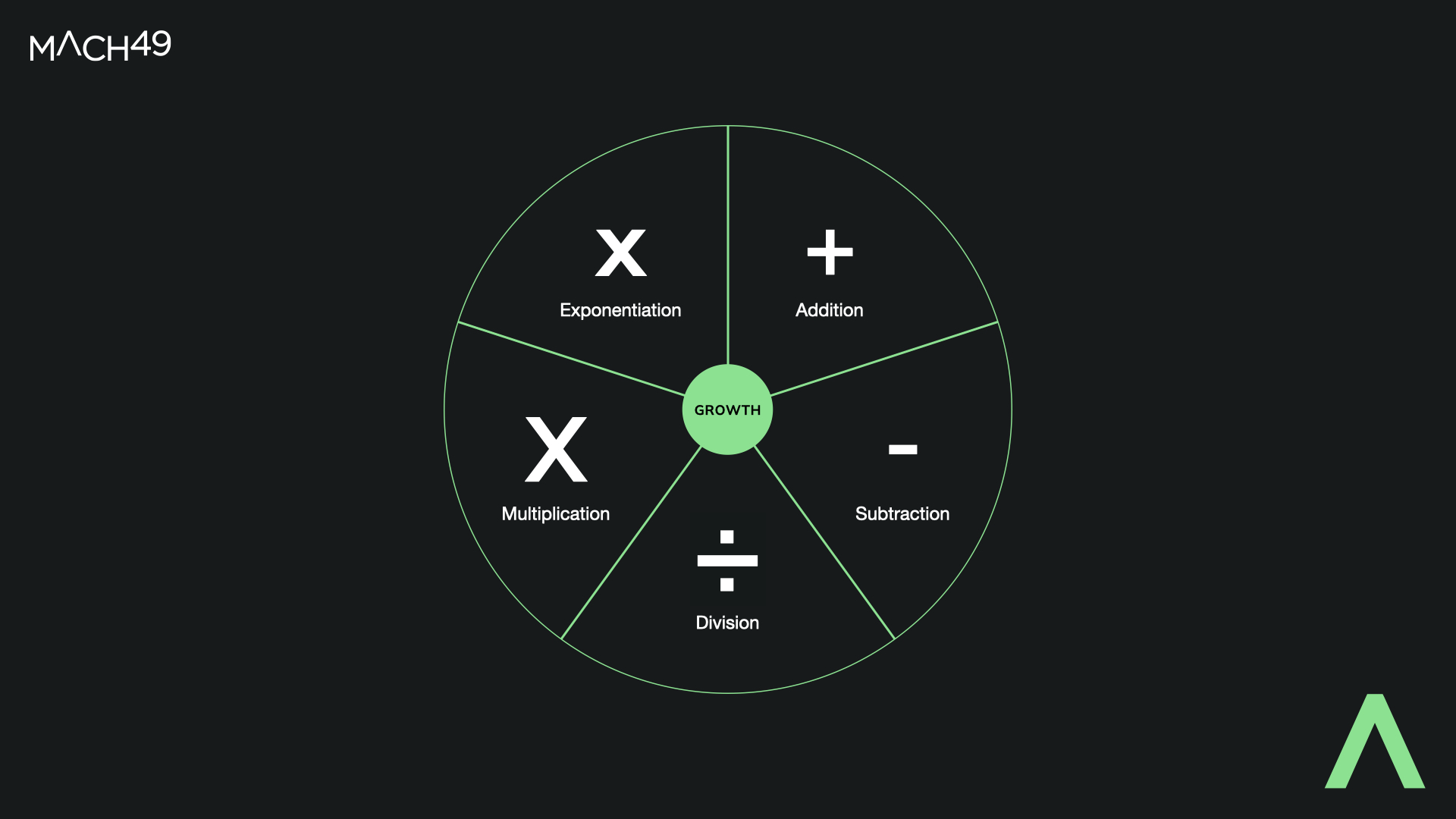

But underneath all that complexity lie five core mathematical “performance zones” – addition, subtraction, division, multiplication, and the most difficult of them all, exponentiation. Each has its own metrics and logic, whether they occur in marketing, finance, operations, purchasing, manufacturing, or HR. But your company’s future may well depend on how effectively you optimize the mix among these five.

Periodically looking at your business through this mathematical lens can help you see if it matches your fundamental strategic agenda, especially when it comes to your company’s future fitness.

The key questions: what math are we really performing today in each arena of our company? Is that the right math for our future?

+ Addition

Companies often think and talk about the future as growth, and growth as an exercise in addition. It’s the logic and language of more - how can we do more, sell more, make more, or work more? On its face, it makes sense. But in fast-changing markets, it can also lead to irrelevance if it results in simply doing more of the same. That’s the mistake most of yesteryear’s leading companies made in the face of insurgents like Apple, Google, Alibaba, or Tencent and their ilk; not to mention their proverbial predecessors, the buggy whip manufacturers.

Additive performance metrics are enticing. They suggest improvements in your status quo – a good thing. And usually not easy to achieve in a complex organization. But those additive metrics can also be deceiving. Especially if the markets, technologies, or regulations you depend on are changing at a faster pace. They may well get to the future before you do.

Growing 5% per year sounds great – unless your market is simultaneously exploding by 15 or 20% annually.

Acquisitions are almost by definition an additive approach to growth, at least initially. But they, too, pose their own challenges when it comes to translating a “1+1=3” deal that looks great on paper into actual results which warrant that initial enthusiasm.

The corporate graveyard is filled with tombstones of acquisitions that didn’t.

What’s the most important question of addition? Are we adding real and/or perceived value to the stakeholders most important to our company’s long-term success? Most often, that’s the equation to solve for your customers, but it also applies to investors and employees. All those parties are asking themselves whether your company is better than their alternatives – to buy from, invest in, or work at.

You might want to treat your “Addition Zones” as necessary but not sufficient if your company needs real transformation to get ready for the future you anticipate. Be aware that too much focus on addition may lull your company into a sense of false comfort.

- Subtraction

This is the other most common form of math in business. It’s usually focused on the resources side. How and where should we cut our costs, reduce our labor force, or scale back our marketing or R&D budgets?

Subtraction is a double-edged sword. It calls for its own form of discipline, because it’s rarely a pleasant math to perform in most situations. Colleagues lose their jobs, pet projects get shelved, or promising initiatives are delayed or shuttered.

Subtraction is often the math of survival – an exercise in “tightening our belts” or “hunkering down” in threatening times. But subtraction can also trigger ingenuity and innovation in your organization. How?

By thinking of subtraction as not simply an exercise in cutting, but in exploring. Sometimes being forced to explore what’s possible when key resources are sharply constrained compels your people to consider entirely new ways of creating value. It focuses your attention and invites your ingenuity.

After all, much of innovation happens in the context of shortage, not surplus.

One thing’s for sure: it’s tough to subtract your way to growth, but subtraction can free up resources to propel real value growth. Think of it like the organizational equivalent of WD40 – a tool to reduce unnecessary complexity in your everyday processes and policies, freeing your attention on what really matters. For more ideas, check out Huggy Rao and Bob Sutton’s discussion of “bad friction” in their new book, The Friction Project.

So, treat these “Subtraction Zones” as possible staging areas for new value creation, but beware relying on them as your primary platform for future readiness.

÷ Division

Adam Smith, the father of modern capitalism, probably loved this math. He viewed division of labor and specialization as the engines of economic progress itself. Would that it were so simple.

Division is required math in most complex organizations. It’s why functions, products, and markets are separated (“divided”) from each other so each can receive the attention they deserve.

The problem is that most of us are better at dividing than we are at coordinating and integrating. Those “divisions” can easily become well-defended silos, and the squabbling among them can turn corporate strategy into a lame version of intramural appeasement masquerading as customer-centric thinking. And it can slow your efforts to streamline your company

In many ways, the hardest challenge in execution today is not competency or specialisation; it’s integration.

That is, how to synchronise, harmonise, and coordinate the self-imposed divisions of our own companies. In some cases, the best answer may well be some form of subtraction to reduce the number of moving parts, or even a more extreme non-mathematical solution borrowed from nuclear energy: fusion.

So, think about your “Division Zones” carefully. Too often, the intramural skirmishing they can foster reinforces market myopia and creates unnecessary complexity. That, in turn, compromises your company’s delivery of meaningful value to your customers and slows your ability to streamline your ship before it enters future waters.

X Multiplication

Several years ago, a science parody radio show in the US asked its variant of the Adam Smith question: how can cells multiply by dividing? Biology has the answer: mitosis – the process by which cells duplicate themselves naturally. But businesses don’t have that self-replicating power. They have to find other ways to not just add, but multiply, value.

The good news? Every business has some forms of value multipliers in its various activities. It may be the multiplier of customer loyalty which can dramatically increase customer lifetime value. Or a shrewd financing structure that allows a company’s cash to be deployed noticeably more efficiently. Or a customer self-service option that disproportionately enables reductions in customer service costs and complexity.

The bad news? Too often companies become too absorbed with addition, subtraction, and division, and lose sight of those precious multipliers. These are the real levers in your business – the resource multipliers that can create powerful competitive advantage and strategic agility.

Your company’s “Multiplication Zones” deserve real support and continued attention. One simple suggestion: ask every functional area in your company to periodically identify the specific value multipliers in their domain and explain the logic (and math) behind each. And then ask whether you are devoting enough resources to those that withstand scrutiny.

X Exponentiation

A tough, unusual word; but this is the real Holy Grail of value creation. In precise mathematical terms it means the operation of raising one quantity to the power of another.

Think about that word: “power.”

Exponentiation is multiplication on steroids. It can generate value not by incremental addition but by multiplying one resource by the power of another . . . over and over again. You might think of it as “compound advantage.”

Imagine if you could apply the transformative power of AI, for example, to a new business model that reduced your working capital requirements or boosted your per-unit profitability. Or multiply a better-targeted market segmentation framework by the power of a redesigned, simpler customer experience. In other words, an advance in one resource might continually reinforce an advance in another.

Those opportunities in your company’s “Exponentiation Zone'' may be hard to find or even imagine, but are well worth searching for in your business. They may hold the key to a stronger foundation for your company – keys that are likely obscured when your team is preoccupied with other math operations.

Imagine a simple C-suite scoreboard with just those 5 “zones,” each performing its primary mathematical operation across your company:

What percent of your resources do you think you’re devoting to which solution zones? What should that mix look like? Are you investing too much effort in addition and subtraction, or overcoming the execution challenges of division – at the expense of looking for turbo-charged multiplication and exponentiation possibilities to best prepare your organization for a tomorrow quite different than their today or yesterday?

Periodically looking at your business through this mathematical lens may give you and your team a new perspective on how you can best solve the essential long-term survival equation for every business:

Sustainable Success = Profitable Growth X Time

Faculty Partner JOHN DANNER teaches at the University of California, Berkeley Haas School of Business, and is a sought-after advisor to Fortune 500 enterprises, mid-market businesses, and emerging ventures worldwide.

/ MORE PERSPECTIVES FROM M49